Article by Júlia de Marins, Learning Coordinator for the Next Generation Climate Advisory Board

In the heart of the Colombian Massif, in Tierradentro (Cauca), the Nasa people maintain a deep relationship between spirituality, music, and territory. Yet in recent years, they have witnessed a rapid disappearance of the jaw—an endemic cane used to craft ceremonial flutes—and, with it, the decline of musical, ritual, and ecological practices central to Nasa culture. In response to this, and to preserve and protect this valuable connection to ancestral culture, grantee partner Kiwe’ Uma’ Cultural Education Process started the Jaw Project.

The jaw (cane flute) grows between the Andean forest and the páramo — a high-altitude ecosystem that covers more than 60% of Colombia’s territory. Both environments are now severely affected by monoculture farming, cattle ranching, and climate change. Due to rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, the jaw, which can take up to 16 years to flower, has become increasingly scarce. This has led young musicians to replace traditional instruments with industrial materials like PVC, which change the sound and weaken youth and community connection between music, ecosystems, and ancestral knowledge.

According to FAO and UNEP (2021), Indigenous Peoples protect 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, even though they occupy only 22% of its land. For Global Greengrants Fund, supporting Kiwe’ Uma’ means investing in the preservation of one of the many Indigenous cultures that are protecting precious biodiversity and ultimately, safeguarding the planet from increased climate crisis impacts.

Connecting Generations

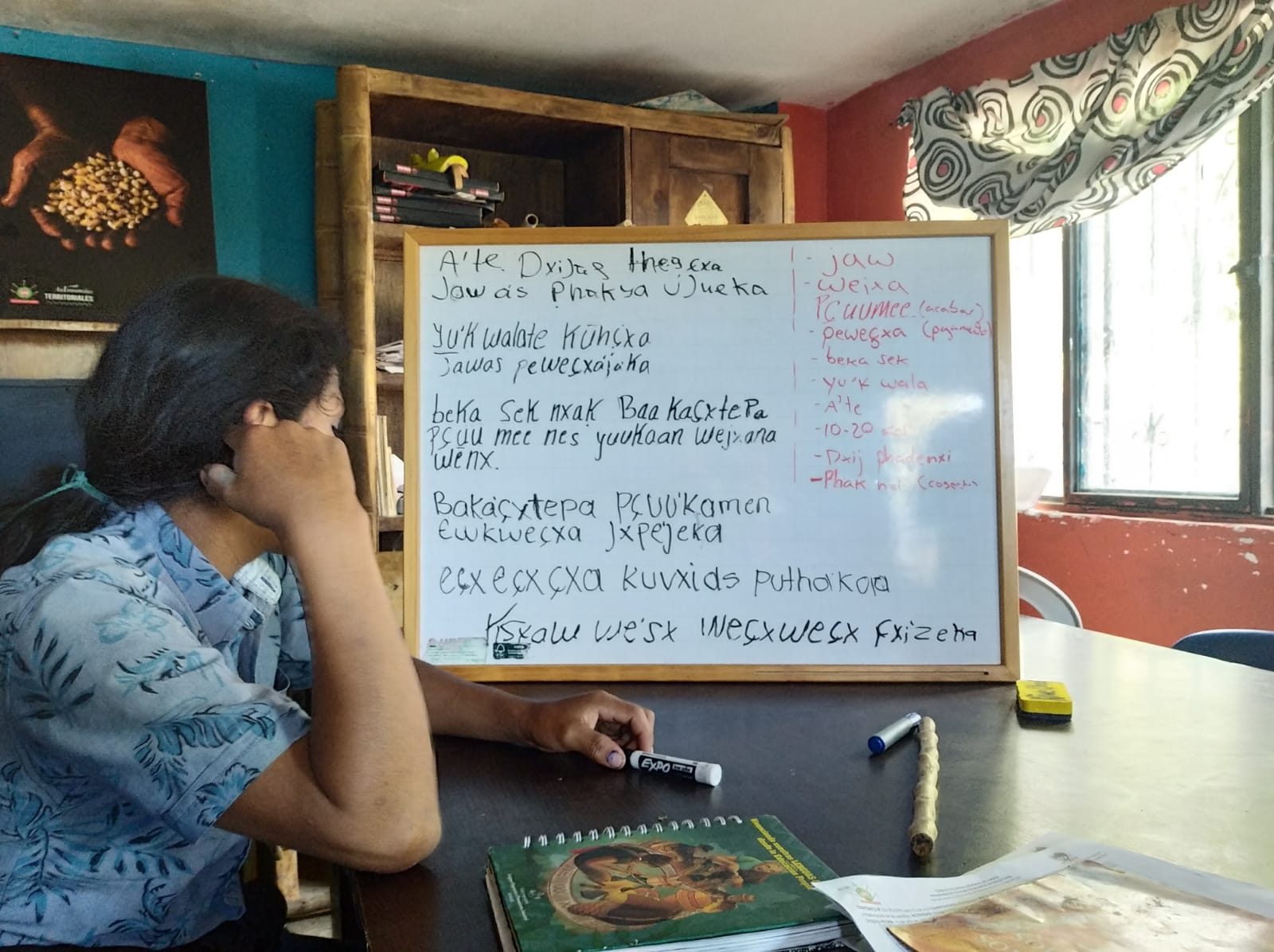

With support from Global Greengrant Fund’s Next Generation Climate Board, the Jaw Project works to revitalize the Nasa peoples’ spiritual bond with the jaw through a community-based learning process. Kiwe’ Uma’ organizes guided walks with elders, where children and youth learn to identify where the jaw still grows, listen to stories about its ritual significance, and discover the right times and methods for harvesting it. Elders and youth also plant cuttings in the Calderas Indigenous Territory as a concrete act of ecological restoration.

Building on this experience, participants move toward the collective construction of instruments. In the tulpa—a traditional learning and meeting space—participants craft flutes from the harvested cane and learn more about flute construction and the flute’s cultural significance. Then, during music workshops with the Chicha y Guarapo collective at the Intercultural Gathering of Ancestral Musical Knowledge in Bogotá, youth create and record three original compositions.

Impact and the Road Ahead

The impact of this work is significant: already, nearly 75 members of the Nasa people (from 15 families) have taken part in the process, including children, youth, parents, and cultural leaders. Elders from five Indigenous territories have also participated actively from the beginning, generously sharing their knowledge. Children have not only learned to make flutes, but also to understand the spiritual value of the jaw and the importance of caring for the ecosystems that sustain it. These intergenerational dialogues offer critical support for youth to carry on ancestral Nasa traditions, which ultimately promote a culture of deep care for the land and its ecosystems.

The Jaw Project is not meant to scale or be replicated mechanically. Its strength lies in its depth and alignment with the Nasa way of relating to the world. When youth plant a cane, blow into a flute, or gather in the tulpa, they are not only recovering a plant, but also regenerating relationships, territories, and possible futures. They are honoring the natural cycles of the moon and the sun, engaging in organic agriculture, managing waste responsibly, practicing eco-construction with local resources, conducting research, and embracing the use of clean energy.

To carry this work forward, Kiwe’ Uma’ will continue to work with the Nasa community to plant jaw, strengthen Indigenous musical groups, and exchange knowledge with other Indigenous communities.

Why Fund Indigenous-Led Projects?

Initiatives like this demonstrate the vibrant, essential knowledge Indigenous Peoples have to offer as salves to today’s socio-environmental crises. The teachings of the Nasa people about natural cycles, the ritual use of local materials, and the connection between music and spirituality invite us to rethink how Western society relates to the Earth.

The story of the Jaw Project underscores that funding youth-led Indigenous projects is not only a politically sound decision, but a climate strategy grounded in evidence. For those of us invested in building climate and environmental justice, that must necessarily include supporting Indigenous youth to carry forward ancient traditions that are rooted in territory, culturally relevant, and truly regenerative.